Table of contents

Browse categories

Browse authors

AB

ABAlberto Boffi

AL

ALAlessia Longo

AH

AHAl Hoge

AB

ABAljaž Blažun

BJ

BJBernard Jerman

BČ

BČBojan Čontala

CF

CFCarsten Frederiksen

CS

CSCarsten Stjernfelt

DC

DCDaniel Colmenares

DF

DFDino Florjančič

EB

EBEmanuele Burgognoni

EK

EKEva Kalšek

FB

FBFranck Beranger

GR

GRGabriele Ribichini

Glacier Chen

GS

GSGrant Maloy Smith

HB

HBHelmut Behmüller

IB

IBIza Burnik

JO

JOJaka Ogorevc

JR

JRJake Rosenthal

JS

JSJernej Sirk

JM

JMJohn Miller

KM

KMKarla Yera Morales

KD

KDKayla Day

KS

KSKonrad Schweiger

Leslie Wang

LS

LSLoïc Siret

LJ

LJLuka Jerman

MB

MBMarco Behmer

MR

MRMarco Ribichini

ML

MLMatic Lebar

MS

MSMatjaž Strniša

ME

MEMatthew Engquist

ME

MEMichael Elmerick

NP

NPNicolas Phan

OM

OMOwen Maginity

PF

PFPatrick Fu

PR

PRPrimož Rome

RM

RMRok Mesar

RS

RSRupert Schwarz

SA

SASamuele Ardizio

SK

SKSimon Kodrič

SG

SGSøren Linnet Gjelstrup

TH

THThorsten Hartleb

TV

TVTirin Varghese

UK

UKUrban Kuhar

Valentino Pagliara

VS

VSVid Selič

WK

WKWill Kooiker

Load Angle Measurement in Synchronous Machines

Georg Ofner

Höhere Technische Bundeslehranstalt Graz-Gösting (HTL BULME)

October 27, 2025

The load angle between the internal induced rotor voltage and the external mains voltage is an essential parameter for assessing and determining operating points for synchronous machines. However, engineers cannot measure this angle directly. Students perform practical laboratory exercises in a new Laboratory for Electromobility at HTL BULME. They use an incremental encoder on the shaft. The encoder helps analyze, define, and visualize the rotor position in DewesoftX.

HTL BULME Graz-Gösting is one of the largest and best-known schools in Austria. It offers education in four main areas: electronics, technical computer science, e-technologies, and mechanical and industrial engineering. Students receive both theoretical and practical training.

Future engineers authentically learn about materials and parts. They also see how things work together through hands-on training in labs and workshops. Modern equipment is key for training. This equipment includes CNC machines, VR glasses, 3D printers, and labs. These labs focus on EMC, renewable energy, production, and measurement technology.

Synchronous machines

Synchronous machines are essential for supplying electrical energy. It is crucial to understand their key operating points. We used a simple circuit diagram (ESB) to build this understanding. It includes rotor voltage UP, synchronous reactance Xd, and mains voltage UN.

The rotor voltage depends on the shaft speed and the rotor-side excitation current. The frequency is related to the number of pole pairs, p—the mains voltage links to voltage amplitude and frequency.

We can create the corresponding mesh equation assuming the consumer counting arrow system.

Using this mesh equation, we can derive a clear vector diagram to describe and evaluate the operating points.

The active and reactive power balances determine the synchronous machine's operating point. The mechanical shaft torque influences the active power, and the size of the rotor voltage influences the reactive power.

The load angle ϑ, which the voltage vectors UP and UN enclose, appears repeatedly in these equations.

As the ESB shows, we can only measure the internal induced rotor voltage UP with open terminals unconnected to the power grid. During operation, the voltage drop UXd at the synchronous longitudinal impedance prevents the detection of UP and, thus, the direct determination of the load angle ϑ.

Before we can operate the synchronous machine, we need to synchronize it. This synchronization requires that the machine system's voltage level, position, frequency, and phase sequence match the main voltage. If this is the case, the voltage vectors of UP and UN are congruent. We can electrically connect the synchronous machine to the network without a current flow: it is synchronous.

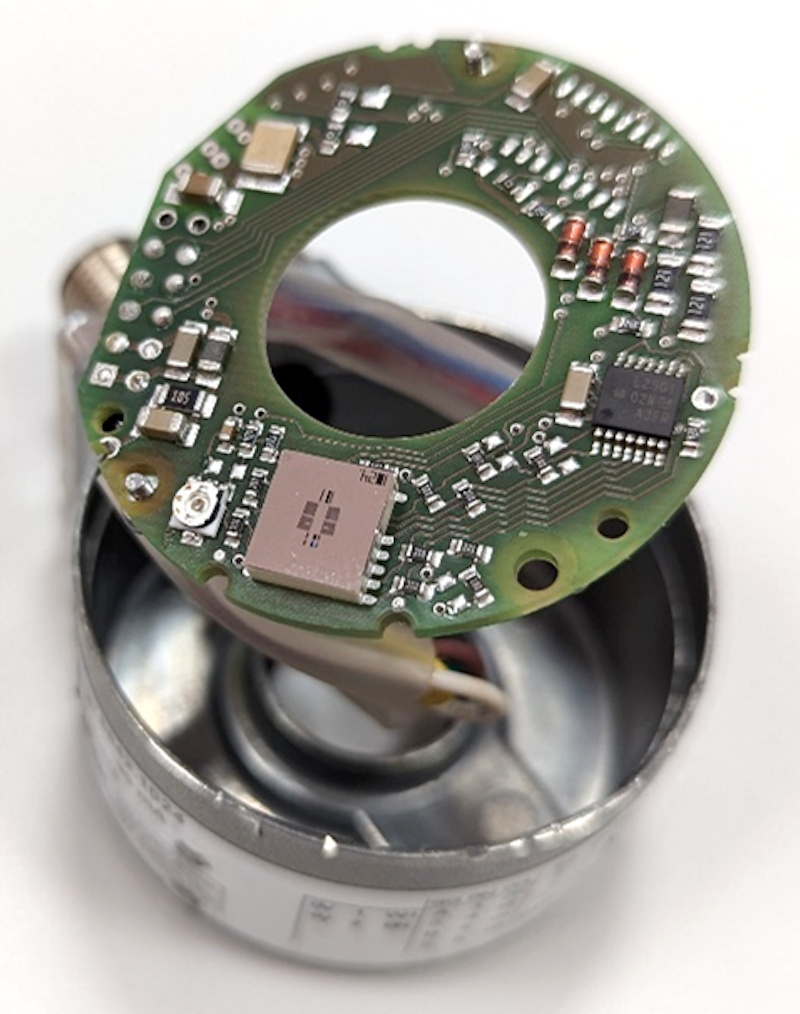

This synchronization process measures the induced pole-wheel voltage uP(t) and generates an identical virtual voltage signal in the math processor. A position sensor measures the shaft's mechanical frequency. In this case, we used an incremental sensor that delivers 1024 pulses per revolution.

We can find the shaft's position or angle in one turn by counting the individual pulses and the zero pulse. We can also measure its speed over multiple turns. We adjust the virtual voltage signal to match the induced pole-wheel voltage uP(t). We use the measured shaft angle and a correction angle until both signal curves are the same.

The mechanical link between the rotor and the shaft is fixed. This fixation means the virtual voltage signal matches the real rotor voltage. This correlation lets us measure the load angle by comparing the mains voltage with this virtual voltage. In concrete terms, we measure the phase shift between the two voltage signals. Depending on the operating point, the virtual voltage can be ahead or behind the mains voltage. In ideal idle mode, both voltages are the same.

It is important to note that both voltage signals have the same frequency. The voltage vectors rotate together because of the magnetic fields from the pole wheel and stator. These fields connect through an imaginary "magnetic spring." Depending on the shaft torque, this spring is tensioned more or less (see formula for electrical power and torque). The theoretical maximum pole wheel angle for a stable operating point is 90°. To avoid the synchronous machine from falling out of step, and for safety reasons, the actual pole wheel angle is significantly lower. We need to consider the number of pole pairs, p. This is important for understanding the relationship between the electrical and mechanical angles of the shaft.

Measurement implementation

Our practical implementation occurs in the new Laboratory for Electromobility, where various drive machines and frequency converters with the associated measuring technology are available. The students work there independently and, under supervision, set up the measuring circuits. They set operating points independently and record measurement data such as current, voltage, and power values. The vector diagram is invaluable and straightforward when measuring power. Here, we can quickly see the set operating point.

We use an intermediate shaft to connect the synchronous machine we study to the load machine. This shaft holds the incremental encoder. The synchronous machine connects electrically to the three-phase network via a special synchronization switchboard. The load machine's torque specification and the DC excitation current set the operating points. The current moves to the rotating rotor through slip rings.

We set up a 4-wire measuring circuit to record the electrical power. The phase voltages are measured directly with the HV inputs, and current clamps measure the current. These clamps provide a voltage signal proportional to the current recorded with the LV inputs.

List of equipment

We use a Dewesoft SIRIUS device for data acquisition and analysis. This flexible and strong data acquisition system offers high-quality signal amplifiers. It works with many signals and sensors. These include:

voltage,

current,

IEPE,

charge,

full/half/quarter bridge,

LVDT,

RTD,

thermocouples,

resistance,

counter,

encoder, and

digital inputs.

The SIRIUS devices can provide a high dynamic range of up to 160 dB, depending on the setup. They also have galvanic isolation. They are available in USB, EtherCAT®, or Gigabit Ethernet configurations. All SIRIUS® instruments come with DewesoftX data acquisition software.

The encoder sends out a high-frequency digital signal. It produces 1024 pulses per revolution at 1500 rpm, which equals 25.6 kHz. The analog inputs cannot capture these pulses quickly enough. Therefore, we use the SIRIUS SuperCounter® inputs for better precision.

These SuperCounter® inputs operate at a speed of 100 MHz. They have a 32-bit resolution and connect through LEMO 1B 7-pin female connectors. The onboard math calculates angle and frequency. It supports modes like Event Counting and Waveform Timing. It also works with angle sensors like Encoder, Tacho, and Geartooth. For more information, see the Dewesoft Online Training Course on Digital Counters.

Hardware:

SIRIUSi-HS-4xHV-4xLV+ running at 20 kHz - capable of 1 MHz sampling rate on analog inputs and 100 MHz on counter digital inputs.

3 x Fluke I30 current clamps, hall principle, measurement range +/-20A.

3 x D9m-BNC adapters.

Software:

DewesoftX Professional - base version, included with the instrument

Power Module - DewesoftX option

Encoders and synchronization

The incremental encoder records the mechanical rotor position. This hollow shaft encoder delivers 1024 pulses per revolution and a zero pulse. This pulse signal is available on tracks A and B, offset by 90° in time. These tracks allow us to determine not only the speed but also the direction of rotation.

We configure the incremental encoder using the corresponding menu in DewesoftX. After a few entries, such as selecting the encoder type, pulses per revolution, and selecting the units, this is complete. The angle and the speed are now available as measurement signals.

To create the virtual pole wheel voltage, we use a formula. This formula draws on the shaft's mechanical angle (see Figure 11). Note that we use radians for calculations and take the number of pole pairs p into account. In our case, this is p=2. The amplitude is not essential since only the phase shift is of interest.

We must create a second identical signal to use the precise and accurate vector diagram for power measurement. This signal should use amperes as the unit. This signal allows us to insert a single-phase power measuring point and display the voltage and current vectors. We can also use the determined phase angle to display the load angle.

Figure 13 shows the time curves before synchronization. The phase shift between the rotor and mains voltages remains synchronous and is visible. The slightly lower rotational speed can identify it. The rotor and the virtual voltage are aligned using a zero-phase angle. The same zero crossings and nearly identical pointers show this.

Figure 14 shows the time after synchronization. A small voltage peak occurs at the moment of connection, after which both voltage curves are identical. The measurement in Figure 15 shows that an ideal idle operation with I=0A does not occur. The measurement data shows that the synchronous machine works like a motor. It drives the train mechanically (P>0, ϑ<0). This relation is also evident from the load angle, which is slightly negative.

Operating points

The following figures show various characteristic operating points:

| Figure | Description of the operating point |

|---|---|

| Figure 16 | Operating point: generator, pure active power |

| Figure 17 | Operating point: generator, over-excited |

| Figure 18 | Operating point: phase shifter over-excited |

| Figure 19 | Operating point: motor, over-excited |

| Figure 20 | Operating point: phase shifter, under-excited |

| Figure 21 | Operating point: motor, pure active power |

| Figure 22 | Operating point: motor, at the stability limit |

| Figure 23 | Unsteady operating point: Tipping with the constant slipping of the machine |

Conclusion

Our study on visualizing and finding the load angle of a synchronous machine provides essential insights. These insights help us understand the operating points and synchronization processes needed to keep the machine stable and efficient. We can use an incremental encoder and math techniques to measure the load angle. This encoder helps us find phase shifts and sync the machine with the grid.

These findings enhance our understanding of synchronous machine behavior and offer practical laboratory applications for students, reinforcing theoretical knowledge and hands-on skills. The results demonstrate the power of advanced measurement and analytical tools in optimizing machine performance and ensuring the reliability of electrical systems.

In the next step, we plan to deepen our calculations using the Dewesoft Motor Analysis plugin.